How do foreign aid commitments to countries experiencing ongoing violent conflict affect the intensity of violence in different regions? One theory is that the formation of lucrative “aid pockets” may create, exacerbate, or prolong violent conflicts. A new AidData working paper, Foreign Aid and the Intensity of Violent Armed Conflict, investigates the impact of foreign aid on the intensity of violence during ongoing armed conflict at a subnational level.

The study finds that the concentration of aid funding in specific regions is associated with higher military fatalities — from pitched conventional battles between rebel groups and government forces for territorial control — but not civilian fatalities. Aid funding that is more geographically diffused is associated with a rise in guerilla warfare strategies, leading to military fatalities lower in number than those from conventional battles.

The concentration or diffusion of aid funding has direct effects on conflict levels. In situations where aid funding is physically concentrated in a few local projects, rebel groups are more easily able to capture and control these strategic points, as opposed to a large area of territory. And when central government officials have the ability to disburse aid funding as a result of their office, the prospect of holding official power becomes highly appealing. This may incentivize rebel groups to seek to capture the seat of government for themselves, leading to more pitched conventional battles between rebels and government forces for territorial control.

Diffused aid that is spread between many projects and across wide swathes of land creates an entirely different set of incentives. Rather than attempt to seize control of the seat of power, rebel groups may instead seek to loot aid funding from these spread-out projects to fuel their ongoing conflict with the government. They may also engage in more violence in the land beyond the central government’s control, where the military does not have as strong a presence and looting for aid is a “safer” activity.

Strandow, Findley and Young used data from two original coding efforts to test whether aid concentrated in areas of ongoing conflict is associated with higher short-term military fatalities than diffused aid — holding the assumption that aid commitments correlate with warring parties’ expectations of future aid disbursements.

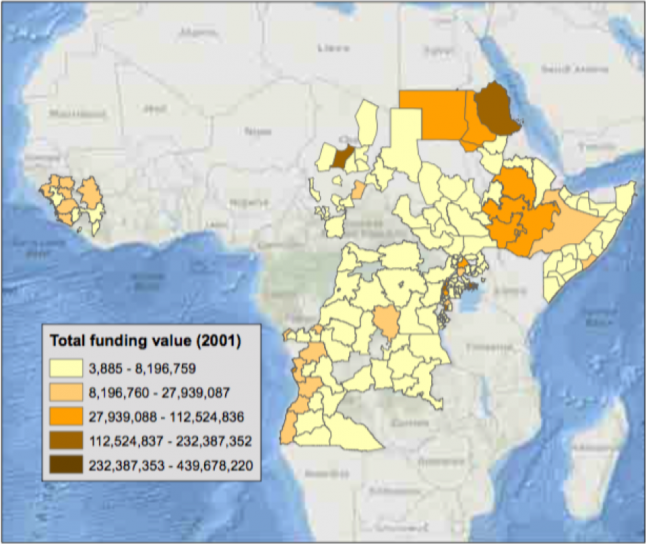

They applied Uppsala Conflict Data Program geocoding methodology to the AidData core dataset to code aid flows within South-of-the-Sahara Africa in conflict years 1989-2008. This aid data was then combined with violent events data (from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s GED sub-Saharan Africa dataset) to produce a dataset that covers affected administrative regions that saw at least one year of intrastate armed conflict that resulted in at least 25 annual deaths. The study is limited in that it only includes aid projects that the authors were able to geocode, the number of which likely differ from the true population of aid projects in the studied areas.

Figure 1: Total Funding Value of Aid (2001)

Their analysis reveals that concentrated aid funding is indeed associated with more short-term military fatalities than in areas where aid funding is diffused. The actual number of military fatalities rose by 138% in cases of concentrated aid funding, equating to about 4 additional military deaths annually, compared to 3 additional military deaths annually in areas of diffused aid funding.

An unexpected finding is that some conventional battles actually arose from government military offenses against rebel groups, not the rebel-led offenses the authors predicted. It may be that the government sought to secure territory that received the most aid funding, or that rebels were simply caught in more conventional battles with government forces as they spent more time in a single location. This finding adds yet another possible mechanism for how foreign aid may spur on or spark conflict.

This granular look at the thorny nexus of aid and conflict highlights some important factors for aid agencies to consider. The author’s findings suggest that concentrating aid funds in specific areas experiences ongoing conflict could increase the number of conventional pitched battles, and thus military fatalities. On the other hand, diffusing aid funding across a similar area could increase guerrilla warfare, while leading to less military deaths than if the aid was concentrated.