Editor’s note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of AidData.

Yemen is enduring one of the gravest humanitarian emergencies of our time. More than 80 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and nearly 20 million people depend on international aid. The health system has collapsed, with preventable diseases and malnutrition threatening millions.

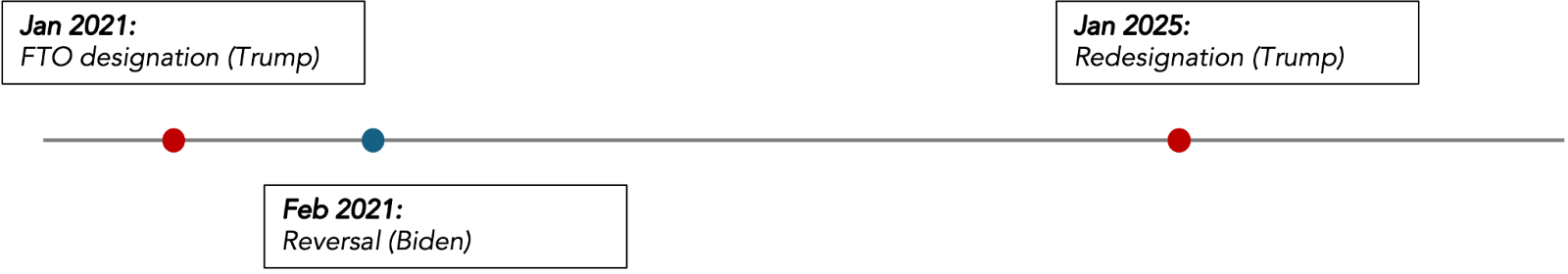

Against this backdrop, U.S. counterterrorism policy added a destabilizing layer of uncertainty. The rebel movement Ansarallah, more commonly known as the Houthis, was listed as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in January 2021, delisted one month later, and re-designated in January 2025. This rapid cycle of listing and reversal created volatility that disrupted aid pipelines, leaving families caught between counterterrorism imperatives and survival needs.

Globally, however, terrorist designations often have the opposite effect: they mobilize more aid rather than less, our research finds. Understanding why Yemen stands out as an exception—as highlighted in our new policy brief—helps illuminate how counterterrorism tools shape humanitarian outcomes, and what policymakers can do to prevent security objectives from undermining basic survival.

Global patterns: When designations trigger aid

We first began by looking at the global picture. Using a dataset of 132 developing countries between 2001 and 2021, we traced how aid flows changed in the years before and after terrorist designations.

The results were striking. On average, development aid increased after designations, especially from institutional donors such as development banks. This finding supports what we call the strategic aid hypothesis: designations elevate the geopolitical importance of fragile states, prompting donors to step in with resources to stabilize conditions, counter extremism, and preserve influence.

But this was not the whole story. Different donors responded differently. Civil society organizations (CSOs) and U.S. humanitarian flows were far more susceptible to the chilling effect hypothesis, which predicts that legal and reputational risks will deter engagement

Compliance burdens, fear of liability, and the stigma of working in areas under a listed group often caused CSOs to reduce their activities even as development banks scaled theirs up.

At the national level, then, designations are rarely associated with aid withdrawal. Instead, they often bring more resources, albeit unevenly distributed across donor types. This makes the Yemeni case all the more remarkable.

Yemen’s exception: Aid disruptions and volatility

Unlike most countries in our study, Yemen diverged sharply from the global pattern. The rapid cycle of listing, delisting, and re-listing created extraordinary uncertainty (see Figure 1). Even before official rules took effect, donors and banks scaled back their activities in anticipation of renewed restrictions. A USAID official noted that “everyone was very concerned and constantly tracking” the possibility of a re-listing.

Figure 1. Timeline of Houthi designations as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) and reversals, 2021-2025

Humanitarian carve-outs existed in law, but they were too narrow and unclear to reassure banks or NGOs. For financial institutions, the reputational risk of non-compliance often outweighed the incentive to facilitate transfers. As one aid worker put it, “you couldn’t just go open a bank account…in Yemen, where there aren’t that many banks, that’s actually a pretty serious obstacle.”

The consequences were most severe in Houthi-controlled areas in North Yemen, home to 70-80 percent of Yemen’s population. Eleven major international organizations suspended or relocated programmes after the 2025 re-designation. In February 2025, the United Nations temporarily paused operations in Sa’ada governorate following the detention of UN personnel, while the World Food Programme suspended key malnutrition prevention activities due to severe funding shortfalls. The combination of these disruptions, U.S. aid cuts, and renewed sanctions enforcement forced several organizations providing nutrition and maternal health support to halt operations in the North. As aid deliveries stalled, local clinics closed, and families reported borrowing heavily just to afford food.

Our subnational analysis of Yemen provided strong evidence of a chilling effect (see figures below). During the pandemic years, aid to both Houthi- and Internationally Recognized Government of Yemen (IRG)-controlled areas fell sharply as global funding contracted. From 2020 to 2021, commitments to Houthi-controlled regions rose again, reflecting donor recognition of acute need. Yet disbursements lagged far behind, likely due to the chilling effect of the 2021 terrorist designation, which created banking restrictions and compliance delays. In contrast, commitments to IRG-controlled areas declined during this period, while the much larger gap between commitments and disbursements in Houthi-controlled areas underscores how legal and operational uncertainty disproportionately constrained aid delivery where needs were greatest.

The institutional divide deepened the crisis. Paradoxically, Houthi ministries often retained more bureaucratic continuity than the internationally recognized government in the South, where high turnover and reliance on political appointees weakened capacity. It was often administratively easier to coordinate aid in the North, precisely where it became most restricted. In the South, where operations were legally viable, weak governance made delivery erratic.

Policy lessons for balancing security and survival

Yemen’s experience highlights the double-edged nature of terrorist designations. Globally, they tend to mobilize aid strategically, but in contexts of volatility and fragmented governance, they can produce severe chilling effects. Three lessons stand out.

First, volatility magnifies risk. The cycle of designation and reversal amplified donor hesitation more than a single, predictable listing. For aid actors, uncertainty is as damaging as restrictive rules. Policymakers must weigh not just the content of designations but their consistency over time.

Second, carve-outs must be credible. Humanitarian exemptions on paper are insufficient if they are vague or poorly communicated. Banks and NGOs need explicit guarantees that essential activities will not expose them to liability. Otherwise, aid will stall even where legal protections technically exist.

Third, invest in governance. Strengthening Yemen’s bureaucratic institutions is critical to stabilizing aid delivery. Investing in the training and retention of female civil servants in the South offers one promising pathway. Women are less likely to emigrate permanently, making them more stable contributors to the civil service over time. Supporting their advancement would not only expand opportunities for women but also build resilience into Yemen’s fragile governance structures.

More broadly, Yemen’s divergence underscores that counterterrorism tools cannot be treated as narrow legal instruments. Their ripple effects extend across the humanitarian system, from banking compliance to geographic inequalities in aid. Policymakers must recognize that when designations disrupt survival, they may also undermine the very stability that counterterrorism measures are meant to protect.

About the Authors

Narayani Sritharan is a Senior Research Analyst at AidData. She is an economist whose research focuses on the intersections of international development, migration, and marginalized communities. Her work often explores the unintended consequences of development projects. She has conducted extensive fieldwork in regions like Nepal, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, and the Philippines, where her interdisciplinary collaborations with numerous disciplines shape her research outcomes. Nara has co-authored several peer-reviewed publications, including articles in Orbis and Third World Quarterly and book chapters on development studies.

Magnus Lundgren is a Senior Lecturer and Associate Professor (Docent) of Political Science whose research focuses on international organizations, armed conflict, and multilateral negotiations. He leads the Folke Bernadotte Academy–funded project, Terror-listing and Mediation in Armed Conflict, and co-leads the Global Governance of Artificial Intelligence project, supported by the Wallenberg Foundations. His work has appeared in leading journals, including the Journal of Conflict Resolution, International Studies Quarterly, and the British Journal of Political Science. A former UN political affairs officer in Bangladesh, Lundgren is also Deputy Director of the Centre for Multilateral Negotiations. During the 2024-2025 academic year, he is a Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo.

Akash Nayak is a student at William & Mary, majoring in Economics and International Relations. As a research assistant with AidData's TUFF team, he tracked Chinese financial flows to developing countries. He has interned with the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, the Bridging Divides Initiative, and was awarded the Critical Language Scholarship. He currently serves as Co-Director of DisinfoLab, an undergraduate research group studying disinformation challenges. His research interests include economic development, disinformation, and democratic backsliding.