Women reportedly make up around half of global agricultural labor. Yet across much of rural Sub-Saharan Africa, women farmers remain on the margins of agricultural innovation. Even as the need for sustainable farming practices is more urgent than ever, women frequently lack the same access to trainings and extension services that their male counterparts have. Recent research shows that, when female farmers do receive equal information and resources and are involved in decision-making, they adopt climate-smart innovative techniques at rates that rival or even surpass those of men.

This disparity is especially consequential in northern Ghana, where women play a central role in household nutrition and crop production. As shifting rainfall patterns and rising temperatures reshape what and how families can grow, women’s knowledge of seed conservation—particularly for staples like sweetpotato—becomes vital not only for farm yields but also for the health and nutrition of the next generation. Ensuring that these innovations reach women farmers, and that their perspectives inform local adaptation strategies, is a prerequisite for truly sustainable progress.

This raises important questions: What are the pathways for knowledge and agriculture technology dissemination? How do farmers in northern Ghana share information about improved cultivation techniques? Do male and female household members draw on the same social networks—or do gendered divides in communication pathways leave women cut off from vital insights?

To explore these questions, a group of AidData researchers—Ariel BenYishay, Chief Economist and Director of Research and Evaluation, Katherine Nolan, Research Scientist and co-founder of our Gender Equity in Development initiative, and myself—analyzed the social networks of men and women in the Generating Revenues and Opportunities for Women to Improve Nutrition in Ghana (GROWING) project implemented by the International Potato Center (CIP), a research-for-development organization with a focus on sustainable root and tuber crops.

The GROWING project organizes men and women into Growing Futures Clubs (GFCs) over three 24–26-month cycles to learn improved dietary practices, marketing and business skills, and sustainable cultivation of orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP)—especially the Storage in Sand and Sprouting (Triple-S) technique, a method that allows farmers to sprout and multiply quality vines at the start of the rainy season by conserving sweetpotato roots during the dry season.

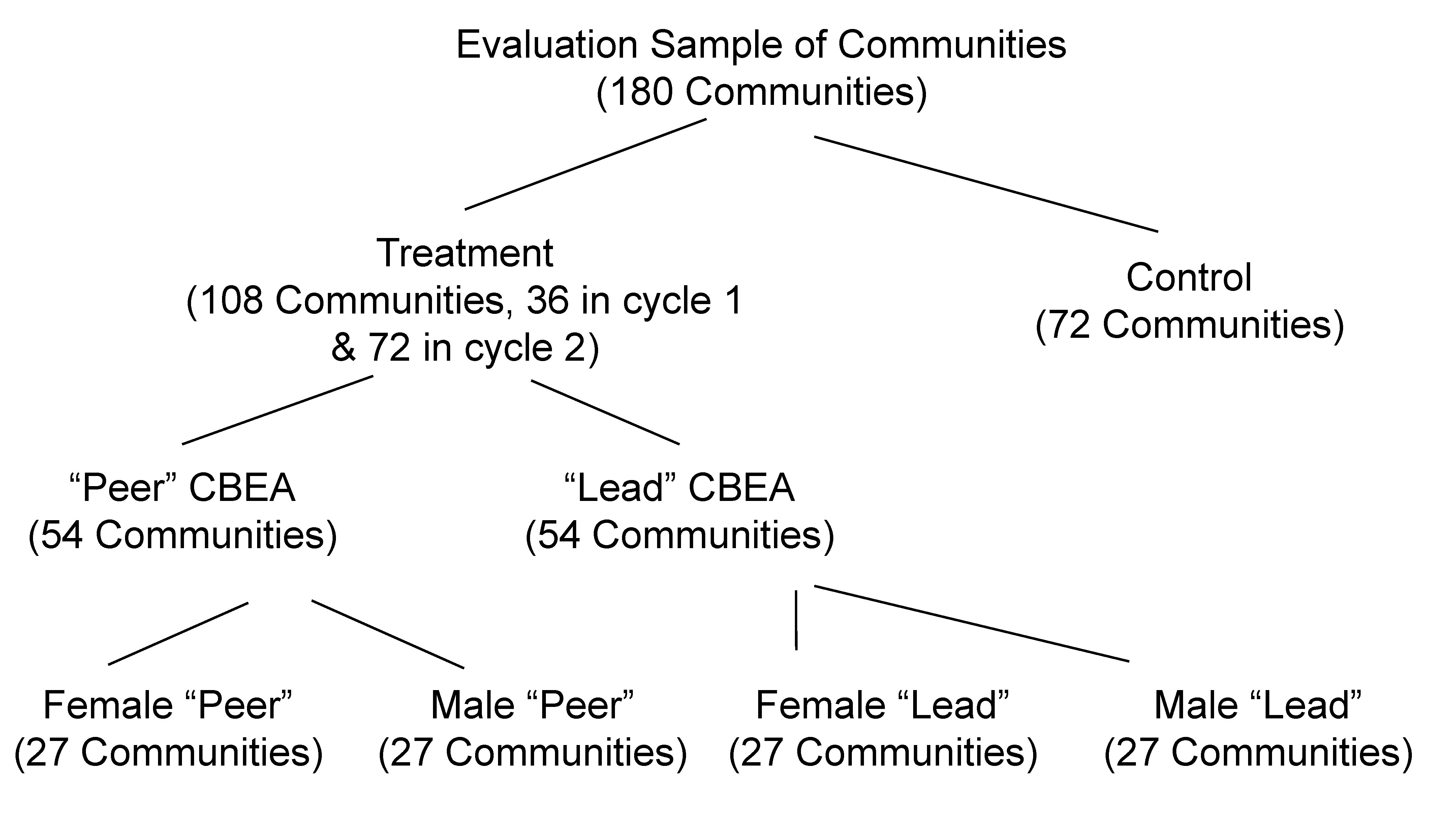

To analyze the influence of gender and social status on knowledge diffusion via the growing clubs, AidData and CIP conducted a randomized controlled trial in which communities were placed into either a control group or four treatment groups that had similar growing clubs, but “community-based extension agents” (CBEAs, farmers trained to support other farmers in agricultural production) with different characteristics. Assigning CBEAs to different groups based on their gender and social status (whether others viewed them as peers versus leaders) allowed researchers to compare discrepancies in knowledge diffusion across groups (such as the uptake of the Triple-S technique) and evaluate the influence of gender and status within the program.

Because the GROWING project aims to spread knowledge through communities, understanding how social networks diffuse information is important for CIP to maximize their impact.

Traditional household surveys tend to nominate a single “head of household”—most often the husband—as the sole respondent. But this approach can conceal intra‑household dynamics (how husbands and wives do, or do not, share information and resources and make decisions) and create proxy‑reporting biases (where data is skewed when one spouse reports on behalf of another that may or may not be accurate).

To paint a more nuanced and accurate picture, AidData’s social network survey collected household-level data from both spouses from 1,806 households in 108 communities across 6 districts in northern Ghana. Our survey captured who couples turned to for advice on agriculture or nutrition, with whom they discussed household responsibilities, and even from whom they borrowed cooking oil. We also asked respondents to list close friends and group members with whom they performed farming tasks, and whether they recognized a list of randomly selected individuals in the community—so that we could understand how large and diverse their social networks were.

Overall, we found that men reported more social links compared to women. This was especially true when it came to men reporting higher rates of agricultural conversations, food sharing, and group participation, as well as being more likely to recognize randomly selected community members, as compared to women.

Since CIP trains community-based extension agents (CBEAs) to support other farmers in the community, we are also interested in the social networks of the extension agents and how these networks could help the community learn innovative farming practices. Our survey showed that farmers who are also CBEAs tended to have more connections with others in the community than farmers who are not CBEAs. Interestingly, whether CBEAs were peers or leaders did not appear to influence their number of links, and female and male CBEAs had similar numbers of social connections.

Farmers, whether they are CBEA or not, tended to know more people within their own gender, according to our survey. As shown in the chart below, about three out of every four connections reported were with someone of the same gender.

Social connections may not overlap, we also found. Spouses shared a median of just two connections—leaving about 80% of husbands’ and 75% of wives’ networks outside their partner’s circle. This suggests a strong need to survey both spouses to capture a household’s full social network. If a research project only surveys the male household member, the results will be biased.

By interviewing both spouses, rather than relying solely on a male head of a household, we were able to obtain a more accurate understanding of the complexity and differences in the social networks of spouses in the same household. This approach highlights discrepancies and overlaps in men and women’s social networks, offering insights into how gender affects patterns of interaction, social influence, and even access to information.

Improving community access to helpful agricultural information is just one benefit of incorporating data from both men and women in household surveys of these development programs. Previous AidData research surfaced similar findings that relying on the head of the household—often the male member—might skew survey data and yield biased estimates. In a survey of both spouses in 1,243 households in northern Ghana, AidData researchers discovered that male and female household members often disagreed on basic facts, such as (1) the number of plots that they farm and (2) who makes decisions on these plots.

To gauge the size of measurement error in surveys that rely predominantly on responses from heads of households, AidData researchers turned to GPS surveys of these households’ farm plots and satellite imagery as a source of impartial knowledge for key plot characteristics. When we compared those objective measurements with what respondents reported, interesting patterns emerged. First, in contrast to women, men tended to overstate the size of plots on which they claim decision-making responsibilities. Second, men often underestimated the distance from home to plots managed by their wives. Third, male farmers were also more likely than female farmers to report production on plots that appear to be fallow (not actively farmed) based on satellite imagery.

These two survey-based studies demonstrate that household members not only have different social connections, but they may also have different answers to survey questions on household assets and decision-making responsibilities. These disparities should remind scholars and practitioners to think carefully about whom to survey and to adjust for sampling bias when relying primarily on male survey respondents as representative of whole households.

By systematically including women’s voices in field data collection—from agricultural extension trials to health and nutrition studies—we can build a more comprehensive picture of community dynamics, leading to more effective and accurate evaluations of development programs. This, in turn, helps ensure that interventions are tailored to the needs and realities of all stakeholders, reducing gender bias in both evidence generation and the policies that follow.