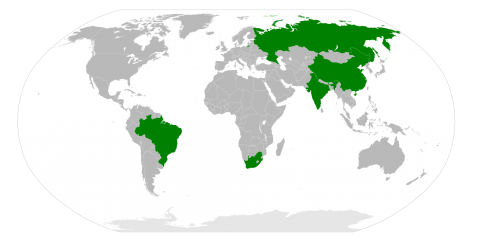

(Courtesy Image: Bidness ETC)

One fundamental question reigned at the 2011 Busan High Level Forum for Aid Effectiveness: would China sign the Busan declaration? The importance of the BRICS, especially China, in development finance was no longer disputed - these countries were key players and their participation in the declaration was essential. Getting them to participate, however, would require moving beyond the narrative of development assistance associated with the Organization for Economic Cooperation’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) and making the declaration more neutral and inclusive. In the end, DAC officials got their signature from China and a loose commitment from non-DAC donors, but only after omitting any mention of Official Development Assistance (ODA) in favor of the term “development cooperation.” The arrival of the BRICS had clearly brought about a fresh start in how we perceive development finance.

The BRICS in the DAC Framework

Efforts to accurately capture the BRICS’ aid portfolio to date have been ad hoc, non-systematic, and non-comprehensive. Although Russia began reporting some of its aggregate aid flows to the DAC in 2011, the BRICS have objected to divulging the entirety of their development finance figures through the OECD-DAC framework and Credit Reporting System (CRS). China, in particular, has raised the strongest objections to the DAC, saying that the DAC framework propagates ‘discredited conditionalities’ and serves as a tool for Western financial institutions to “set the rules” of the global economic system - a system in which developing countries, lead by the BRICS, are increasingly taking center stage. On the other hand, this perceived lack of transparency to OECD-DAC standards has triggered accusationsthat the BRICS are being unduly secretive and intentionally misleading.

This perceived lack of transparency doesn’t tell the full side of the story of BRICS donors. The current definition of ODA may not capture the entire essence and scope of their development cooperation, which is rooted in the wider South-South Cooperation (SSC) principles of mutual interest and respect for national sovereignty discussed previously in this series.

China and India: Blind Spots in the Status Quo

China and India are helpful case studies to illustrate why the DAC’s definition of development assistance is inappropriate for BRICS donors.

China’s tied aid, like that of the Chinese Export-Import Bank’s resource-backed loan to Angola in 2004, has clear developmental intent and is often “deeply concessional in character”, more so than loans provided by Western banks. However, this lending still does not qualify as ‘development assistance’ according to the OECD. Moreover, China embeds its development cooperation within wider ‘external assistance’ packages that include the advancement of commercial ventures and the transfer of military aid, in line with the broader scope of South-South Cooperation. Because development cooperation is nested within these larger packages, it is ultimately not considered ODA. Similarly, India channels its aid through lines of credit that maintain high enough concessionality rates to qualify as ODAbut are not treated as such because their primary intent is to promote trade and investment for South-South Cooperation, despite their clearly development implications.

Scholars and policymakers have suggested several solutions to address the lack of representative data on the BRICS’ development finance and the deficiencies in the current DAC-OECD definition of ODA:

- Create a unique, separate standard of reporting for the BRICS that co-exists with the DAC structure.

- Allow multilateral entities, such as the United Nations, to create and administer a universal repository for aid information.

- Challenge the DAC framework with one that prioritizes the values, principles, and frameworks of the SSC.

Participating countries in BRICS (World Bank)

The BRICS Development Bank: New Horizons

While there has been limited progress towards implementing any of these potential solutions, BRICS countries in the meantime are developing some of their own approaches to resolving existing issues. One such approach is the BRICS’ active attempt to present an alternative to the existing development assistance infrastructure, allowing them to influence the trajectory of development finance while gaining greater representation in the global arena. The New (BRICS) Development Bank (NDB) formed in July 2014 - coinciding with the 70th anniversary of the establishment of Bretton Woods - is being perceived as a legitimate alternative to the World Bank and IMF for developing countries. Each participant has infused it with US$10 billion in starting capital, for a total of US$50 billion, to finance infrastructure and ‘sustainable development’ projects. In addition, the BRICS have put forward a US$100 billion Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) to make foreign reserves available for times of economic shocks or crisis.

Operational challenges continue to exist with the NDB. There is also the potential for philosophical disputes, as the differing economic and political systems of the BRICS may affect the types of regimes that they choose to support and the manner through which they provide aid. Additionally, definitional disagreement about development cooperation among the BRICS may impede collaboration. In particular, BRICS countries define ‘sustainable development’ in different ways.

Moving Forward: Ground for Compromise?

Despite emerging rhetoric, the NDB is not positioned to be a direct challenge to the World Bank and IMF; rather, it will likely complement them or present an alternative in times of economic crisis. In this way, the NDB and increasing prominence of the BRICS countries underscore the need to consider seriously their development strategies and role within the larger aid framework. If we want to move beyond a signature, a standard definition of development cooperation is needed that more fully encompasses the contributions of BRICS countries.