In the aftermath of any disaster, coordinating emergency response funds and providing personnel for relief as quickly as possible is crucial to minimizing the damage. On April 25th, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake and aftershocks devastated the country of Nepal, injuring or killing thousands, and the immediate relief response was swift as Young Innovations’s Open Nepal portal has tracked over $830 million in relief aid pledged so far. In addition to monetary assistance, though, the situation in Nepal witnessed the advent of another aspect of aid in disaster response.

As Nepal is a mostly rural, extremely mountainous country with poor road infrastructure, delivering much-needed aid to remote areas from the country’s only international airport in Kathmandu in the aftermath was made difficult by the lack of detailed geospatial data available in most satellite maps. This is where AidData came in: our students and staff worked with partners on the ground to collect and deliver geo-referenced data to relief workers on the ground through the open-source mapping platform OpenStreetMap. This data was and continues to be valuable to leaders, donors, and workers in Nepal, and it offers important insights about the future of “data responders” to disaster. But it also provides insights about how integral maps are to relief, especially in remote, disaster-prone countries.

This summer, five student researchers traveled to the Philippines as AidData Summer Fellows to work with the recently launched Map the Philippines initiative led by Making All Voices Count, learn about existing geospatial technologies and help develop a new open source, open data mapping platform. As one of our Fellows Lu Sevier told us, “the Philippines is currently ranked third in the world for countries with highest risk for natural disaster,” and though natural disaster seems imminent for the country, there are things that can be done to prepare.

Making an Impact in the Philippines

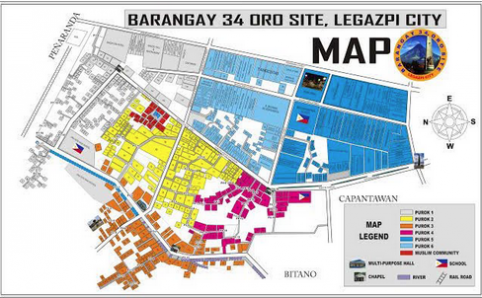

In one barangay, or neighborhood, in Legazpi City, mapping has already made an impact. Despite being under a volcano and in the middle of a typhoon zone, the residents here have not experienced casualties due to disaster in five years; an unheard-of phenomenon in this locale. One way residents have prepared for an emergency situation was by mapping the entire neighborhood by hand in great detail. As Lu told us, the map allows residents of the barangay to locate women and children, avoid flood-prone areas, and move to designated evacuation centers quickly.

(The detailed map one barangay leader created in case of disasters or emergencies)

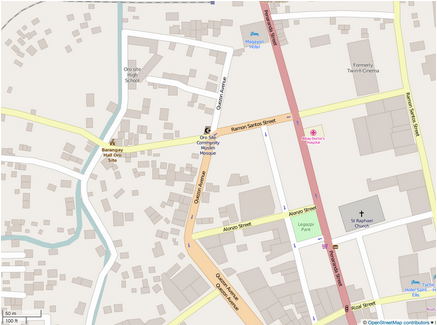

Though the map is currently in a static JPEG format, it can be translated to geocoded spatial data where anyone can access it and add to it in real time. Lu told us that she sat down with the leader of this community and transferred the map on to OSM in the span of 25 minutes. They haven’t added all of the buildings and other details the original map contains yet, but the Fellows are planning to lead a workshop on the collaborative mapping wiki soon so that the whole barangay can be mapped and everyone can access the information quickly and easily in case of an emergency.

(The same barangay as it appears on OpenStreetMap)

Open Source, Open Data After Disasters

OpenStreetMap is a collaborative project dedicated to creating a free, openly editable map of the world. It was established to counteract map falsities due to protective copyright policies and general restrictions on geospatial data availability, and thanks to its dynamic, interactive interface it has been dubbed the “Do-It-Yourself Mapping Project.”

This source has the potential to be extremely useful to disaster relief efforts because anyone can add a multitude of different features to it in real time. AidData used it in creating our Nepal information portal and our Fellows in the Philippines are now leading workshops to train university students and community members in the Philippines how to use it as well.

OSM’s potential applications are practically endless, and its reach is universal. One of its significant potential applications is real-time geocoding for disaster relief efforts, an action taken on by the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team several times in the past. The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team worked with over 600 volunteers and civilians in Haitito create a detailed basemap for organizations responding to the 2010 earthquake. In 2014, the project partnered with Médecins Sans Frontières and others to identify potential travel routes of the Ebola virus in West Africa.

OSM does not have to be a tool only for response after disaster, though. Tan Teck Boon and Allen Lai recently published an article in International Policy Digest reviewing disaster preparedness as it stands in Southeast Asia, and the three most significant problems they saw were “state interference,” relief agencies lacking “the capacity to accurately assess a disaster situation,” and poor “coordination between disaster relief providers.” The essential problem here is a lack of collaboration and communication between significant players ahead of time and during the response; the problem is closed data.

When data on relief efforts and maps of at-risk locations are made open, the development community is able to analyze current disaster response plans and potentially make them better. Local community members can visualize evacuation routes and centers to make them safer and stronger, and organizations can coordinate plans to make sure supplies and personnel are distributed in the most efficient way possible.

Open data also enhances the transparency of aid organizations, a quality in need of improvement after the poor handling of $10 billion worth of aid pledged to Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. Though the international community rallied quickly to respond to this disaster, information about the actual use and distribution of pledged money was largely hidden or unclear, so a large chunk of what was pledged actually went to overhead costs rather than Haitians’ needs. Making data on these kinds of costs clear allows us to make sure aid is disbursed properly, and see where more help is needed.

Creating open source maps can improve reaction time after disasters as well, since people on the ground can update the conditions of roads and buildings to help responders find the safest, most efficient routes in and out of critical areas. It is vital to create immediately available, open sourced maps like AidData’s living Nepal portal and the barangay’s OSM because they save time and energy for aid providers.

As Lu says, “when there’s a disaster, you don’t have time to wait on the phone,” and in these cases, open maps can save lives, too.