AidData (aiddata.org), a research lab at U.S. university William & Mary, today released a new flagship report and massive dataset that comprehensively tracks China’s lending and grant-giving activities worldwide. The scale and scope of Beijing’s portfolio is vastly larger than previously understood: $2.2 trillion of aid and credit spread across 200 countries in every region of the world.

For the first time, AidData is publishing detailed and comprehensive information about China’s secretive lending and grant-giving activities in high-income countries like the U.S., the UK, Western European countries, Japan, and Australia, in addition to the world’s developing countries.

“The overall size of China’s portfolio is two-to-four times larger than previously published estimates suggest,” said Brad Parks, AidData’s Executive Director and the lead author of the report. The over three-hundred-page-long publication—Chasing China: Learning to Play by Beijing's Global Lending Rules—finds that more than three-quarters of China’s overseas lending operations now support projects and activities in upper-middle income countries and high-income countries. “Much of the lending to wealthy countries is focused on critical infrastructure, critical minerals, and the acquisition of high-tech assets, like semiconductor companies,” said Parks.

China is pulling back from its role as an aid provider that champions philanthropic causes. Instead, AidData researchers find increasing alignment between China’s cross-border lending activities and the policy priorities of the party-state, including those related to national security and economic statecraft. Meanwhile, its financial operations are becoming more opaque and complex, with many transactions using shell companies in pass-through jurisdictions with strict banking secrecy rules.

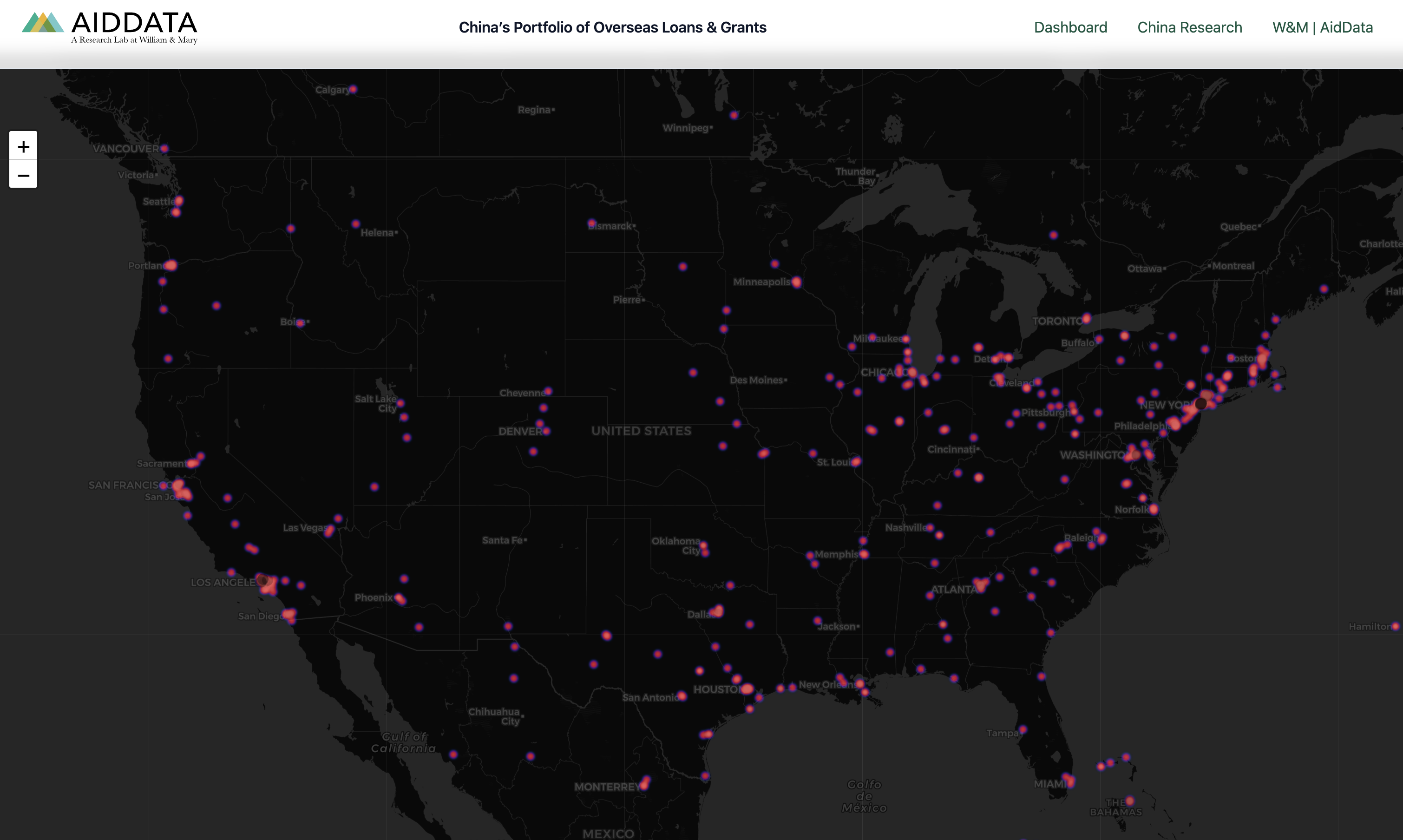

Among the findings, the U.S. has received more than $200 billion for nearly 2,500 projects and activities that can be found in virtually every state in the country.

The United Kingdom received $60 billion. The European Union’s 27 member states received $161 billion for nearly 1,800 projects and activities. Among the top deal-making countries are Germany ($33.4 billion), France ($21.3 billion), Italy ($17.4 billion), Portugal ($11.7 billion), and the Netherlands ($11.6 billion).

The results of the AidData’s 36-month effort have relevance beyond the rarefied air of high finance, with implications for geoeconomic and national security strategy. The report touches on topics as sensitive and varied as the vulnerability of strategic commodity reserves, the reliability of power plants and transmission grids, the control of international maritime chokepoints, the resilience of global supply chains, and national competitiveness in high-tech sectors. Although governments and alliances (like NATO and the G7) are in open competition with Beijing, AidData finds that many Western or Western-led financial institutions have chosen to collaborate with Chinese state-owned creditors—and many Western companies have borrowed large sums from the same institutions.

According to AidData’s research team, increased competition among the world’s great powers is spilling over into the aid and development finance sector: “We are witnessing a fundamental reorientation away from the promotion of economic development and social welfare in recipient countries—as a primary goal—and towards the promotion of the economic competitiveness and national security of aid and credit providers,” said Brooke Escobar, Associate Director of AidData’s Tracking Underreported Financial Flows team and a coauthor of the report. “Beijing is not seeking to burnish its reputation as a global do-gooder: the percentage of its overseas lending and grant-giving portfolio that qualifies as aid (ODA) has plummeted. It is focused on cementing its position as the international creditor of first—and last—resort that no one can afford to alienate or antagonize,” said Escobar.

The new global dataset is based on a massive effort involving more than 140 fact-finders and financial analysts. It tracks more than 30,000 projects and activities from 1,193 Chinese donors and lenders via grants and loans worth $2.2 trillion across 217 countries and territories between 2000 and 2023. During this 24-year period, 200 countries and territories received at least one grant or loan from a Chinese donor or lender. AidData researchers also identified 2,610 co-financing institutions—including Western and non-Western commercial banks, multilateral financial institutions, and bilateral development finance institutions and export credit agencies—that collaborated with Beijing on overseas projects and activities. It is the most comprehensive dataset of its kind, anywhere. At the same time and for several reasons that are described below, it is becoming increasingly difficult for AidData and other research institutions and think tanks to uncover what China is bankrolling—and how it is doing so.

Chasing China busts the myth that Beijing’s overseas lending operations have plummeted to record lows. In fact, the newly collected data show that China remains the world’s largest official creditor, lending approximately $140 billion to public sector and private sector borrowers around the globe in 2023. “China has never fallen below the $100 billion a year threshold since the Belt and Road Initiative, its flagship global infrastructure program, was first announced, which means that it has remained the world’s largest official creditor for at least a decade,” said Sheng Zhang, a coauthor of the report and Senior Research Analyst at AidData. “In 2023, Beijing outspent Washington on a more than two-to-one basis and it outspent the World Bank—the single largest multilateral source of aid and credit—by nearly $50 billion.”

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery

Chasing China describes how Western powers, rather than forging their own path, are seeking to compete with Beijing via mimicry. G7 member countries are following China’s lead and adopting its playbook. They are shuttering or slashing the budgets of foreign aid agencies, fast-tracking loans with national security justifications, taking equity stakes in critical infrastructure and critical mineral assets in overseas jurisdictions, and bailing out financially distressed sovereigns.

The report’s authors note that the Trump administration recently took a page out of Beijing’s playbook by tapping the U.S. Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund to provide a $20 billion bailout—through a currency swap facility—to the Government of Argentina. The Biden and Trump administrations have also sought to bankroll the acquisition of ownership stakes in critical infrastructure and critical mineral assets in high-income countries—such as Greece’s Piraeus Port, Greenland’s Tanbreez rare earths deposit, the Panama Canal, and Australia’s Darwin Port—on national security grounds.

After the recent dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), legislators in Washington are considering a U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) reauthorization bill that would increase the agency’s lending cap from $60 billion to $250 billion and give it a freer hand to operate in high-income countries on projects of national security significance. Questions are also swirling about whether the DFC might adopt the collateralization practices of Chinese state-owned creditors.

Beijing’s go-it-alone approach has forced policymakers in Western capitals to fundamentally rethink the way they use aid and credit instruments. But China has one major advantage, according to the AidData team: the ability of the party-state to align the overseas priorities and activities of Chinese companies with its policy directives. In 2015, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) adopted a policy called “Made in China 2025” (MIC2025) that seeks to ensure China’s dominance in a wide array of high-tech manufacturing sectors—including, but not limited to, artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, semiconductors, quantum computing, 5G, biotechnology, and renewable energy. Since the adoption of MIC2025, AidData finds that the percentage of China’s cross-border acquisition lending portfolio targeting “sensitive” sectors has skyrocketed from 46% to 88%.

AidData also finds that Beijing’s playbook for getting overseas mergers and acquisitions approved in sensitive sectors has proven remarkably successful. Its long-run, average success rate is 80%—and it has increased over time. According to the authors of the report, Beijing has done so by focusing its efforts in countries with relatively weak screening mechanisms for inbound foreign capital. It has also “flown beneath the radar” of regulators, auditors, and counterintelligence officials by channelling funds through offshore shell companies and international bank syndicates.

China’s financial footprint in the United States

According to the AidData research team, between 2000 and 2023, Chinese state-owned lenders extended roughly $943 billion of credit to high-income countries. No country in the world accepted more official sector credit from China than the United States.

“This is an extraordinary discovery, given that the U.S. has spent the better part of the last decade warning other countries of the dangers of accumulating significant debt exposure to China, and accusing China of practicing ‘debt trap diplomacy,’” said AidData’s Executive Director Brad Parks.

Chinese state-owned entities are active in every corner and sector of the U.S., bankrolling the construction of liquid natural gas (LNG) projects in Texas and Louisiana, data centers in Northern Virginia, terminals at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York and Los Angeles International Airport in California, the Matterhorn Express Natural Gas Pipeline, and the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline. They have financed the acquisition of high-tech companies, such as a Michigan robotics company, the infrastructure and automotive business of Silicon Labs, Complete Genomics, and OmniVision Technologies. U.S. recipients of liquidity support from Chinese state-owned creditors—via working capital and revolving credit facilities—include a wide array of Fortune 500 companies, including Amazon, AT&T, Verizon, Tesla, General Motors, Ford, Boeing, and Disney.

Chinese loan- and grant-financed projects and activities in the United States, 2000-2023

Beijing goes into “dark mode”

The authors of Chasing China find that the obstacles to tracking Chinese lending and grant-giving are increasing over time, making the job of AidData and other independent researchers in this space ever more difficult. “We find evidence of a 62% decline over time in the availability of information from official sources about China’s overseas lending and grant-giving program,” said Katherine Walsh, a coauthor of the report and Senior Program Manager at AidData. “Our ability to access unredacted loan contracts between Chinese state-owned creditors and foreign borrowers increased between 2010 and 2022, but then sharply declined between 2022 and 2023.”

Beijing appears to be taking steps to limit oversight. These measures, according to AidData’s research team, include routing funds through shell companies in offshore financial centers, requiring stringent confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements, outsourcing public-facing roles to non-Chinese entities, and redacting large swathes of text in transactional documentation.

The Chasing China report also provides evidence that Beijing is pivoting toward more exotic credit instruments that are more expensive and difficult to track—and far less likely to appear in audited financial statements, stock exchange filings, and bond prospectuses. According to Walsh, “the cross-border finance landscape is becoming substantially more opaque, at a time when transparency is more needed than ever.”

Slashing aid, deprioritizing the Belt and Road

For many years, China was focused on infrastructure projects in the Global South, with much of its lending undertaken under the auspices of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The report details how the BRI and China’s overseas lending program are no longer one and the same. Beijing has dramatically scaled back its lending for infrastructure projects in BRI participant countries, while ramping up the provision of cross-border credit via liquidity support facilities to countries that do and do not participate in the BRI. For every four dollars that China lends for infrastructure projects in developed and developing countries, it lends another six dollars for overseas projects and activities that have nothing to do with infrastructure. Beijing’s portfolio has also become less BRI-centric over time: infrastructure project lending once accounted for 75% of the portfolio, but now it accounts for less than 25%.

AidData finds that, in a typical year, China spends only about $5.7 billion on what can be strictly defined as aid. Its official development assistance (ODA) budget puts its spending on par with that of a donor like Italy. However, in 2023, China’s global ODA commitments fell to $1.9 billion—their lowest level in two decades. The China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) and China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), which jointly coordinate and administer the country’s foreign aid programs at the direction of the State Council, account for a vanishingly small fraction of China’s overseas lending and grant portfolio. State-owned commercial banks, state-owned enterprises, state-owned policy banks, and the central bank are responsible for more than 95% of the portfolio.

About AidData’s China research program and the new datasets

AidData’s research team drew upon more than 246,000 sources to build the new dataset. These sources include (1) unredacted grant agreements, loan agreements, and debt restructuring agreements; (2) the annual reports, financial statements, stock exchange filings, and bond prospectuses of borrowing institutions; (3) official records extracted from the aid and debt information management systems of host countries; (4) reports published by parliamentary oversight institutions in host countries; (5) IMF Article IV reports and World Bank-IMF debt sustainability analyses (DSAs); (6) annual reports published by Chinese state-owned banks; and (7) direct correspondence with finance and planning ministry officials in recipient countries. The team faced a formidable set of obstacles, including shell companies incorporated in jurisdictions with strict banking secrecy rules, confidentiality clauses that shield contractual terms and conditions from public view, and large swathes of blacked-out text in transactional documentation.

With the addition of high-income countries to AidData’s data collection and analysis efforts, some re-organizing and re-naming of datasets has taken place:

- AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance (GCDF) Dataset is now the China’s Loans and Grants to Low- and Middle-Income Countries (CLG-LMIC) Dataset. It continues to systematically track financial and in-kind transfers from official sector institutions in China to every low-income, lower-middle income, and upper-middle income country and territory in every major world region. There have been three earlier versions of the GCDF dataset: 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0. The latest (1.0) version of the CLG-LMIC Dataset captures 23,816 projects and activities in 142 low-income and middle-income countries supported by grant and loan commitments worth $1.22 trillion (in constant 2023 U.S. dollars) between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2023.

- The 1.0 version of the China’s Loans and Grants to High-Income Countries (CLG-HIC) Dataset captures 9,764 projects and activities in 72 high-income countries supported by grant and loan commitments worth $943 billion (in constant 2023 U.S. dollars) between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2023.

- These two new, fully interoperable datasets jointly provide global coverage of China’s overseas loan and grant commitments. However, for those seeking a unified view of China’s grant and loan commitments across the entire world, AidData has produced an integrated data file, which it refers to as the 1.0 version of its China’s Global Loans and Grants (CLG-Global 1.0) Dataset.

By the numbers

- 16 full-time researchers and 126 part-time research assistants spent more than 36 months on the data collection and analysis.

- The newly collected data were assembled with 246,261 sources in more than a dozen languages.

- Each record in the CLG-Global 1.0 Dataset is underpinned by an average of 7.3 sources—and more than 88% of the records are supported by at least one official source. These official sources include a vast trove of unredacted grant agreements, loan agreements, debt restructuring agreements, debt cancellation agreements, mortgage agreements, escrow account agreements, deeds of covenant, deeds of security, share pledge agreements, and commodity offtake contracts, among other types of transactional documentation.

- The new dataset tracks more than 30,133 projects and activities supported by 1,193 Chinese donors and lenders via grants and loans worth $2.2 trillion across 200 countries and territories between 2000 and 2023. By comparison, AidData’s groundbreaking November 2023 report introduced and analyzed a dataset of 20,985 projects and activities financed by 791 Chinese donors and lenders via grants and loans worth $1.34 trillion across 165 low-income and middle-income countries.

- The newly collected data also provide an extraordinary amount of geographical detail regarding where Chinese-financed projects take place. For 14,192 projects that have physical footprints or involve specific locations, AidData is now able to identify point, polygon, and line vector data via OpenStreetMap URLs.

AidData puts all its data and analysis in the public domain, for free. To expose its coding and categorization determinations to public scrutiny and promote replicable research findings, AidData also discloses all sources used to construct the dataset—at the individual record level.

MEDIA CONTACT: Alex Wooley, AidData Partnerships and Communications Director; awooley@aiddata.wm.edu; +1.757.585.9875.