China’s oil-backed lending involves a simple exchange: cash today, oil tomorrow. Beijing’s contracts in Venezuela follow a common blueprint found in many resource-rich and often politically isolated governments, including Angola, Ecuador, Iran, and Iraq.

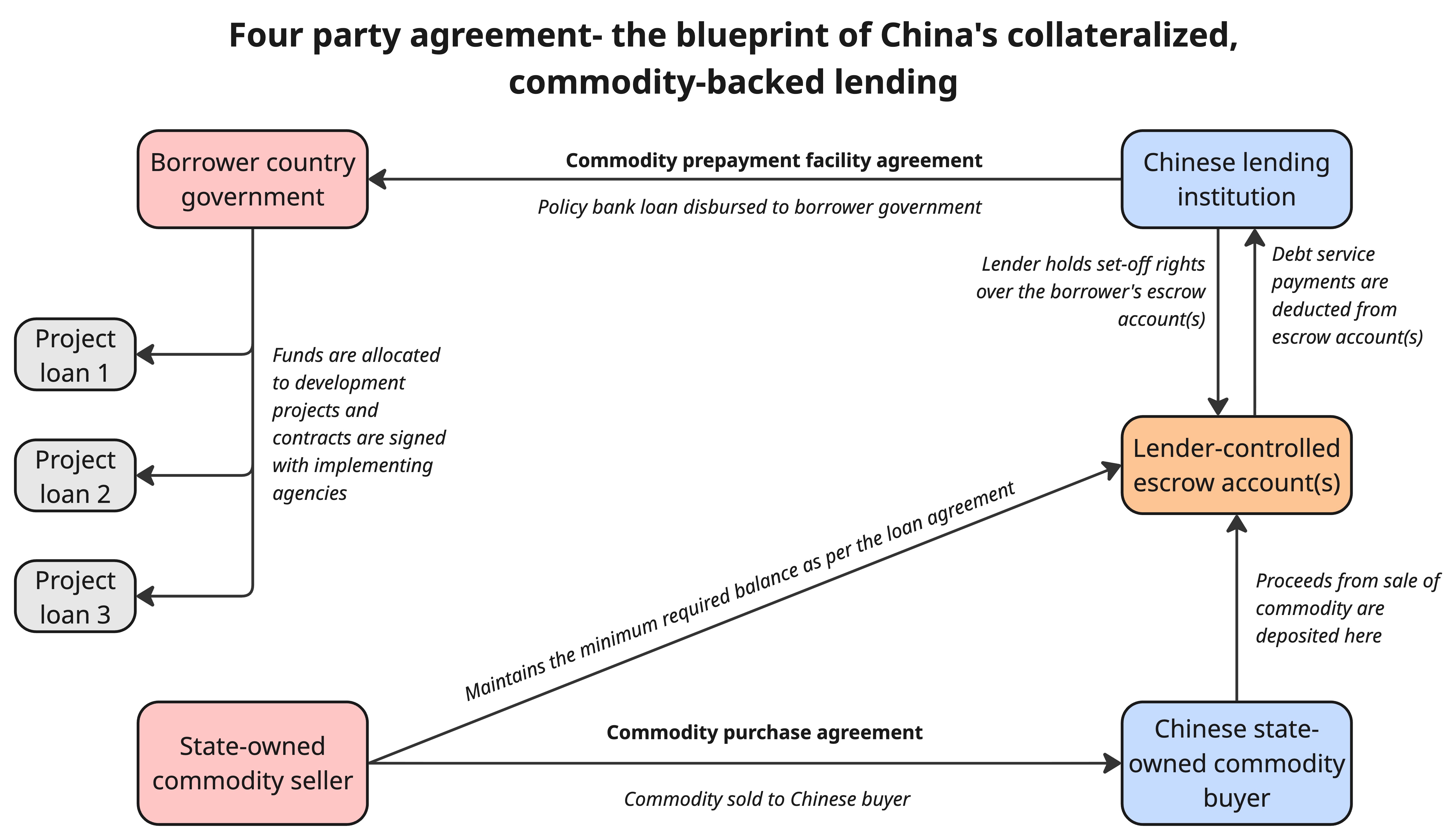

The blueprint links three elements: a Chinese policy bank to loan the money, a commodity purchase contract requiring the borrower to sell commodities (sometimes at a pre-agreed price or quantity) to a purchaser in China, and a repayment channel that directs commodity sale proceeds toward debt service. This structure allows the borrowing government to mobilize large capital infusions across multiple sectors while relying on a single revenue stream for repayment. Beijing, in turn, secures preferential access to the energy supplies it is scouring the globe to obtain.

In the case of Venezuela, China Development Bank, the world’s largest development finance institution, financed the loans. The commodity purchase contract involved Venezuela's state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA) and a Chinese state-owned commodity purchaser. And the repayment channel was the proceeds from PdVSA’s revenue stream from oil sales.

Home to the world’s largest known oil reserves, Venezuela was perceived as a safe bet for China’s commodity-backed lending model. However, with repeated spells of debt distress and political uncertainty in the aftermath of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s capture by the United States, Beijing’s multi-billion dollar bet has turned sour.

China has supported commodity-linked borrowing in several resource-rich countries, often tied to their leading export commodities—such as bauxite in Ghana, copper and cobalt in Zambia, and platinum and tobacco in Zimbabwe. The appeal for both the borrower and the Chinese lender is scale, speed, and a repayment design funded by export proceeds often supported by supply contracts with a known buyer. These structures can also suit governments that are politically isolated and face tight financing constraints.

Previous research by Bradley Parks, AidData’s executive director, and others demonstrates that in these Chinese deals, “collateral” is often broader than the project itself. Revenue from oil or other commodities backs borrowing that finances transportation, industrial inputs, or spending on social welfare programs. In that sense, one revenue stream supports many activities.

But while borrowers gain access to large cash infusions, risks are concentrated for creditors. Such lending arrangements rely on the sustained profitability of the underlying commodity—in Venezuela’s case, oil. Venezuela shows what happens when that hinge point fails: nearly a decade ago, a collapse in both global oil prices and Venezuela’s oil production exposed the fragility of a lending model built on a single, increasingly unreliable source of repayment.

Venezuela is the single largest recipient of Chinese state-backed lending in Latin America and the fourth largest globally. AidData’s China's Global Loans and Grants Dataset, Version 1.0, which covers 2000 to 2023,records 106 Chinese loan commitments to Venezuela totaling $105.59 billion. The vast majority of these loans ($95 billion) were structured to have oil-backed repayment.

These loan commitments occurred exclusively between 2000 and 2018. This scale makes Venezuela a useful case study for understanding how contract design interacts with market shocks and sanctions. The breakdown began years ago, as oil prices fell and Venezuela’s repayment stress escalated. The outcome was not a single rupture. It was a sequence of sovereign defaults, debt restructurings, and sharp fluctuations in oil prices that dwindled governmental revenues.

A deep-dive into the China-Venezuela lending structure

The majority of Beijing’s lending to Venezuela lending occurred through the Joint China-Venezuela Fund, signed in 2007 by former Chinese President Hu Jintao and his Venezuelan counterpart, Hugo Chavez. The Joint Fund, a central feature of Chinese lending to Venezuela, ultimately led to the collapse of their financial relationship.

At first, the Joint Fund provided a steady flow of funding from China for Venezuelan development projects—growing from $6 billion in 2007 to $60 billion in cumulative loan commitments by 2015. The Joint Fund makes up 58.7% of Chinese public and publicly-guaranteed debt in Venezuela. Any large-scale changes that would challenge the repayment terms, payment channels, or enforcement conditions would therefore shape outcomes for the majority of Venezuela’s debt to China.

Four-party agreement and cash-flow controls in the Joint China-Venezuela Fund

The borrower-side institutions in the Joint Fund included the Government of Venezuela and a Venezuelan state bank, Banco de Desarrollo Económico y Social de Venezuela (BANDES). China Development Bank’s contributions amounted to over $60 billion in loan commitments. (While counterpart funding was provided by FONDEN, a Venezuelan state-administered fund, its precise contributions are unknown).

Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), a Venezuelan state-owned oil and gas company, is the seller of oil barrels that ultimately service debt owed by BANDES to China Development Bank. CHINAOIL is a Chinese state-owned commodity buyer that purchases oil barrels from PdVSA. These oil sale proceeds were routed through a collection or escrow account domiciled in China, opened with China Development Bank on behalf of BANDES, the borrower. BANDES is responsible for ensuring that timely debt service payments in U.S. dollars are deposited in the collection account.

Crucially, these oil revenues deposited in the collection account must be held at a minimum required balance. This provides the creditor (China) with easy access to those cash deposits, which serve as collateral. China Development Bank in turn holds “set-off rights” over the collection account—meaning that if BANDES defaults, China Development Bank can apply the cash balance toward overdue debt service by sweeping funds from the account.

Timeline, scale, and scope of Chinese funding

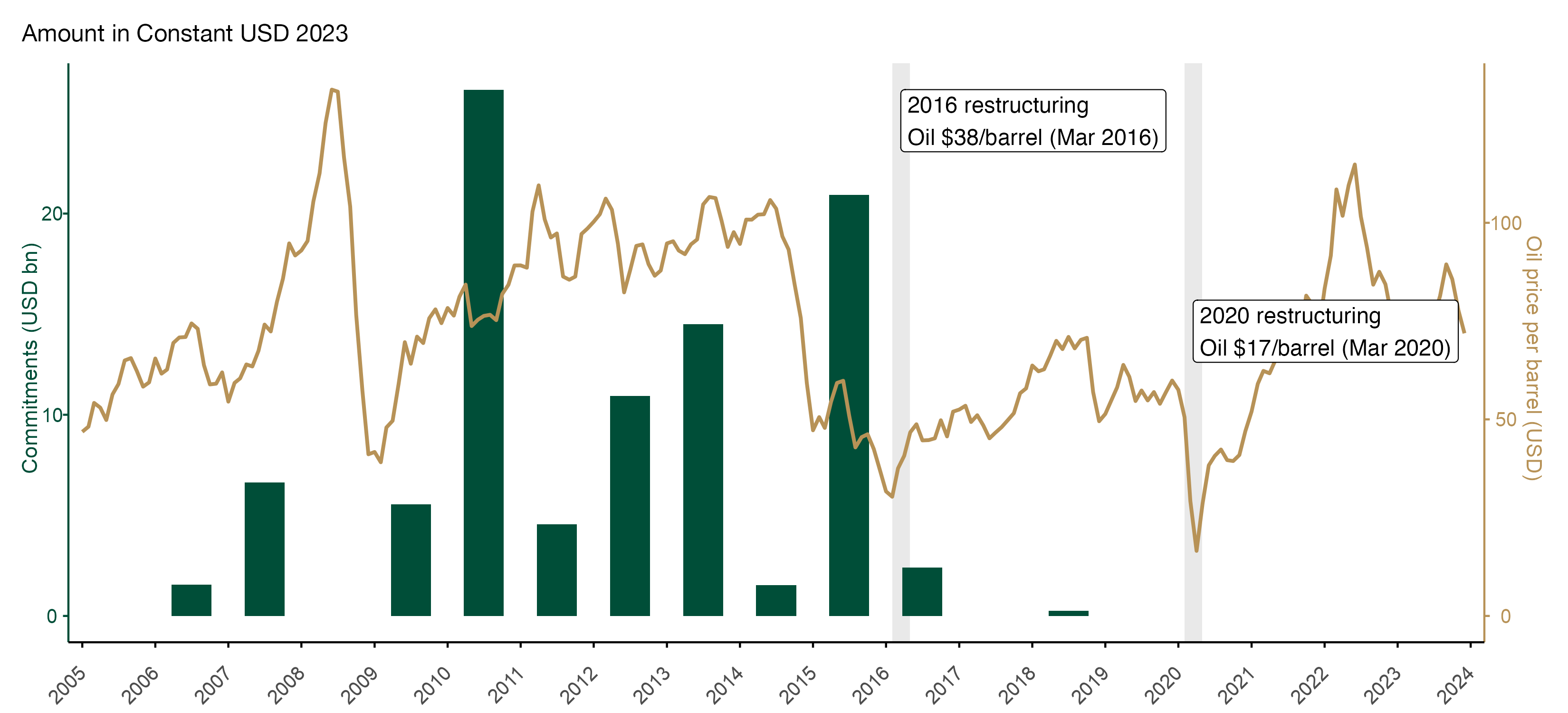

China’s lending to Venezuela was concentrated in the late 2000s and early 2010s, before external pressure and market volatility exposed cracks in the lending structure. The China-Venezuela Joint Fund was disbursed in four tranches across multiple years, as depicted in the figure below. A tranche is one slice of a larger financing facility, issued at a specific time with its own size and repayment terms. Tranches A, B, and C were issued in 2007, 2009, and 2013 respectively. Tranches A and B were renewed twice between 2011 and 2015, upsizing the Joint Fund by $17 billion.

Timeline of the Joint China-Venezuela Fund

.jpg)

These tranches held three-year maturities. A fourth tranche issued in 2010, the Large Volume Long Term Financing Agreement (LVLTFRA), carried a ten-year maturity. The LVLTFRA totaled $20 billion and was split into two currency portions: $10 billion denominated in US dollars and RMB 70 billion denominated in Chinese renminbi. In practice, this meant that most Joint Fund exposure remained dollar based, while a smaller share was RMB based. Between 2007 and 2015, over $60 billion was disbursed through the four tranches.

The Joint Fund supported a wide range of non-oil projects, including those in the transportation, industry, energy, and agriculture sectors. For example, one LVLTFRA tranche financed a $682 million loan for Socialist Agricultural Development Schemes, implemented by the Ministry of Popular Power for Agriculture and Lands, to strengthen crop and livestock production supporting industries such as construction, electrical, transport, packing, and refrigeration (rather than oil production).

The Joint Fund is characterized by cross-collateralization, with multiple debts being tied to the same oil export proceeds via a collection/escrow account, creating interconnected obligations. Gelpern et. al define cross-collateralization as a lending scenario where the same asset or pool of assets secures multiple debts. In Venezuela, oil export proceeds routed into a collection or escrow account effectively served as shared security across multiple obligations—even when financed projects were outside the oil sector.

In parallel, PdVSA borrowed more than $19 billion directly from China Development Bank between 2009 and 2018 for general corporate purposes, or about 18.9% of Venezuela’s publicly guaranteed debt to China. PdVSA also raised significant external financing elsewhere during this period, which added to its overall debt burden. PdVSA thus carried a “double exposure,”meaning that any stress in PdVSA’s operations and revenues could weaken repayment capacity for sovereign debt incurred through the Joint Fund and its direct debt from China Development Bank.

How China’s bet in Venezuela went sour

The Joint Fund linked repayment by tying oil export proceeds through lender-controlled accounts, while allowing Venezuela to allocate financing across multiple sectors, including infrastructure and public investment. However, that design created a built-in tension. Debt repayment depended on one volatile revenue stream, the oil sector, while spending was dispersed across projects that did not reliably generate revenue.

Debt distress built up quickly alongside sharp fluctuations in oil prices. As prices fell sharply after 2014, each barrel generated less cash for debt service. The repayment model then required either higher shipment volumes or deeper fiscal tradeoffs. Venezuela’s heavy crude also traded at discounts, which reduced realized revenue even when headline prices were higher.

Oil-backed lending in Venezuela versus oil price per barrel

The figure above shows that the first major restructuring in 2016 occurred during a low-price period, when crude oil fell as low as $30 per barrel. By 2016, Venezuela’s repayment capacity was under visible strain and the risk of default was rising. China responded with liquidity relief rather than a full resolution. The 2016 restructuring provided breathing room through a principal payment moratorium. This approach fits a broader pattern in China’s crisis response—providing short-term cash-flow relief in the expectation that conditions will eventually improve.

But that expectation did not hold. PdVSA’s revenues continued to deteriorate in the years that followed, and repayment pressures intensified. Principal arrears accumulated. Sanctions then compounded the crisis by disrupting the payment channel itself. In 2019, U.S. measures directly targeting PdVSA tightened constraints on shipments, counterparties, and financial routing. This led CHINAOIL to halt oil purchases in 2019 and 2020. Caracas’ dependence on oil revenue for servicing Chinese debt made default an inevitable outcome.

A second restructuring followed in 2020, as Beijing sought to provide much-needed debt relief. By then, the combination of declining oil revenue and sanctions further constrained repayment logistics. China provided additional relief through a moratorium on principal payments. The 2016 and 2020 restructurings reflect Beijing's familiar strategy of extending time and reducing near-term pressure to prevent default. Despite these adjustments, China’s Venezuela exposure has remained in prolonged distress, with estimates of over $10 billion in outstanding debt stock. The outlook is now even more uncertain after the events of early 2026.

What happens next?

Against this backdrop, Venezuela’s repayment path is riddled with challenges. Statements by the U.S. and American actions to control Venezuelan oil sales have added new uncertainty about repayment outcomes, including for Chinese claims. If U.S. authorities control export sales and the routing of proceeds, PDVSA may have less or even no ability to direct oil revenues toward servicing Chinese debt.

If PdVSA continues operating and routing oil revenues, China would still have several options for settlement based on past relief approaches. First, it could renegotiate away from a repayment regime that hinges on oil sales, as seen in China’s deal with Ecuador. Second, it could offer further restructuring through maturity extensions, principal deferrals, or (in some cases) face-value reductions that write off a portion of the outstanding principal. Third, it could explore currency and settlement changes, such as shifting some debts from U.S. dollars into RMB settlement, which could modestly reduce interest and payment frictions.

Venezuela shows how a collateralized lending model can go off-script when core pillars, such as stable oil revenues or reliable payment routing, fail. Ultimately, whether China can recover value from its long-troubled lending to Venezuela depends on how U.S. control over oil flows evolves and how willing and able Beijing will be to adapt its repayment frameworks to a far more constrained and politicized environment.